Watch this interview and listen to this interview with Lena.

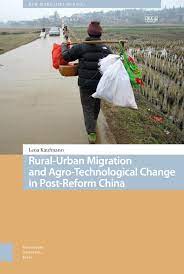

Rural-Urban Migration and Agro-Technological Change in Post-Reform China (open access) investigates how rural Chinese households deal with the conflicting pressures of migrating into cities to work as well as staying at home to preserve their fields as safety net. Since the 1980s, about one fifth of the entire Chinese population has migrated within China, most of them to the big cities on the east coast. This corresponds to more than one third of Chinese farmers. In their places of arrival, most of these migrants work under highly precarious conditions. It is therefore crucial for them to preserve their resources at home as a safety net, especially their fields. However, this is particularly challenging for rice farmers, because paddy fields have to be cultivated continuously and by a sufficient number of people to retain their soil quality and value. Farming households therefore pursue a range of social and technical strategies to deal with this predicament and to sustain both migration and farming.

The book sets out, in a first step, by analysing the important policy and knowledge transformations since the 1950s that have given rise to the particular situation that farmers currently face. In a second step, it describes farmers’ contemporary responses to these transformations. Special attention is paid to the widespread, although commonly overlooked adoption of post-Green Revolution farming technologies that have not only set free agricultural labour and contributed to inducing farmers to migrate, but also given farmers new options for dealing with their predicament. Methodologically, the book draws on ethnographic fieldwork, including participant observation in rural and urban China and interviews with staying and migrating household members, as well as on written sources such as local gazetteers, agricultural reports and statistical yearbooks. Moreover, it also draws on proverb collections as a channel of knowledge transmission.

The book argues, first, that paddy fields play a key role in shaping farmers’ everyday strategies. Scholars from various disciplines have repeatedly stressed that fields play a crucial role in, and for, migration. Yet, the specific socio-technical challenges in preserving this key asset and the knowledge needed to do so remain largely unexplored. This book scrutinizes these challenges in more depth, proposing the need to look at the repertoires of knowledge that both staying and migrating farmers revert to.

Related to this, second, it argues that ostensibly technical farming decisions are always also social decisions that are closely interlinked with migration decisions. In taking seemingly operational decisions, farmers are actually pursuing various long-term and short-term projects that best match their current, fluctuating household situation. What looks like simple technical ability is, in fact, multi-dimensional reasoning for potentially manifold purposes. Applying skills practically and economically always includes simultaneously performing social responsibilities. This means that farming decisions also take into consideration aspects like educational, career, or marriage aspirations, child or elderly care, long-term engagements and future responsibilities and, more generally, the social and economic reproduction of the household and the patriline.

Overall, the book argues for the need to pay more attention to the material world of migration and the related knowledge and skills. It proposes that socio-technical resources are key factors in understanding migration flows and the characteristics of migrant-home relations. In the case of China, for example, a focus on such resources helps to explain why there are so many divided households, why migration is often circular, why relationships with home remain important, and why most migrants envision returning to rural areas in the future.

The book is located at the intersection of the literature on the anthropology of migration, agriculture, and skilled practice. On an empirical level, rather than focusing on the well-studied phenomenon of migrants in their places of destination, it provides a rare qualitative-ethnographic study of migrants’ origins and, in particular, the rural side of Chinese migration. Since the reform policies of the 1980s, Chinese mobility has sharply increased, both domestically and transnationally. In view of this augmented mobility, the book provides new socio-material insights relevant to understanding the most widespread pattern of migration within contemporary China: rural-urban migration from the inner provinces to the large cities of the east coast, which often results in households whose members reside separately in different locations. Focusing on the role of farmland in migration, this book contributes a new perspective on why this pattern remains so common. This entails comprehensively examining both those who stay and those who migrate, and acknowledging that both are part of a rural-urban farming ‘community of practice’. The members of this community of practice are connected through circular migration, embodied farming skills and joint efforts to preserve home resources.

Moreover, perceiving migration in this way lets us rethink the implications of China’s hukou system of household registration, which has strictly divided the population into either rural or urban, agricultural or non-agricultural since the 1950s. This system has long prevented rural Chinese from gaining permanent settlement rights or any entitlement to the welfare, pension and education system available to registered urban-dwellers. The recent reform of China’s hukou system in 2014 increasingly allows rural people to move and obtain an urban registration. In this regard, the book is part of a new strand of scholarship that discusses not only the obvious constraints, but also the advantages of being registered as ‘rural’. Highlighting the central role of land and land entitlement, it contributes to understanding why many rural inhabitants refuse to change their status into ‘urban’ citizens despite having lived in cities for years, and why the peasant smallholder model remains important, despite massive urbanization.

On a theoretical level, the book contributes especially to a recently-established subfield of migration studies, materialities of migration. It contributes to the material turn in migration studies a perspective on things that stay – paddy fields – and the related embodied skills. The latter are important socio-technical aspects of migration that, nevertheless, generally escape our attention because they usually remain tacit and are mostly transmitted beyond formal educational structures. Nevertheless, as the book suggests, such a socio-technical perspective is highly valuable for studying migration phenomena, as a way to offer new understandings of migrant-home relations and dynamics.

Finally, the book challenges prevailing narratives about backwardness and progress. Challenging public discourse which portrays Chinese peasants as passive and backward, it shows that farmers are, in fact, forward-looking decision-making agents who are actively shaping China’s modernity. Overall, this book provides rare insights into the rural side of migration and farmers’ knowledge and agency.

Author Bio

Dr Lena Kaufmann is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Zurich, where she is a research associate in both the Department of History and the Department of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies. Trained as an anthropologist and sinologist in Rome, Berlin and Shanghai, she holds a PhD in social anthropology from the University of Zurich. She spent four years in China and has conducted extensive research on Chinese migration in urban and rural settings. She is the speaker of the Regional Group China of the German Anthropological Association. Her current research project focuses on Swiss-Chinese entanglements in digital infrastructures. She can be reached via email at lena.kaufmann@uzh.ch.