- Faculty members and university administrators/managers who are based at Xiamen University (XMU). This includes staff who travel regularly between the two campuses, or staff who have taught/worked at XMUM for a short period of time (e.g. on secondment, on temporary visit or exchange).

- Faculty members and university administrators/managers who are based at Xiamen University Malaysia (XMUM). This includes local and international staff who were recruited directly to XMUM or seconded from XMU.

- Students at Xiamen University Malaysia (XMUM). This includes local and international students enrolled in Foundation or Degree programmes.

Category: Uncategorized

Conference on Transnational Higher Education and Belt and Road Initiative

Where: University of Manchester, Manchester, UK (Ellen Wilkinson Building)

When: 8 November 2018, 11.00 am – 5.00 pm

To register to attend, please go to Eventbrite: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/transnational-higher-education-and-the-china-belt-and-road-initiative-tickets-49421289407

For questions, please contact the conference organising team:

Miguel Lim (miguelantonio.lim@manchester.ac.uk ),

Heather Cockayne (heather.cockayne@manchester.ac.uk) and

Helen Chan (choenyin.chan@manchester.ac.uk).

Conference Programme

China-to-UK Student Migration and ‘Green’ Behaviour Change: A Social Practice Perspective

Tyers, R., Berchoux, T., Xiang, K., & Yao, X. Y. (2018). China-to-UK Student Migration and Pro-environmental Behaviour Change: A Social Practice Perspective. Sociological research online, 1-23. Online first

Dr Roger Tyers, University of Southampton

Abstract

Significant life-course changes can be ‘windows of opportunity’ to disrupt practices. Using qualitative focus group data, this article examines whether the life-course change experienced by Chinese students migrating to the UK has an effect on environmentally impactful practices. It does so by examining how such practices are understood and performed by Chinese and UK students living in their own countries, and contrasting them with those of Chinese students in the UK. Using a social practice framework, these findings suggest that practices do change, and this change can be conceptualised using a framework of competences, materials, and meanings. The findings show meanings – the cultural and social norms ascribed to pro-environmental behaviour – to be particularly susceptible to the influence of ‘communities of practice’ where immigrants and natives mix, with pro-environmental behaviour change resulting from assimilation and mimesis rather than normative engagement.

中文摘要

我们相信,通过审视重大的生活环境的改变可以窥探人们某些行为中断的原因。本研究正是基于此假设而设计和实施的。在本研究中,我们讨论了中国大学生的环境保护意识和行为是否在来到英国留学后而有所改变。

我们采用了小组访谈和讨论的方法, 收集了中国本地大学生和中国留英大学生对不同的环境保护的意识和行为的理解。为了对比的 方便,我们还就同样的话题,询问了英国本地大学生。在数据分析上, 本研究借用了社会行为分析框架,并采用了纯质性分析。

研究结果表明:中国大学生的环境保护行为在出国留学前后确实发生了变化,这一变化能进一步地被“能力-材料-意义”这一社会行为分析框架所解释。其中,我们发现“意义”——关于有利于环境保护的文化和社会规范——受到了主体所在环境的“群体行为”的影响。具体地说,中国留英大生的环境保护行为会模仿当地人群,进而在行为上被同化。这种模仿和同化的作用,比理解和实践相关法律法规条文对行为改变的作用更加直接。

When students leave home to go to university, they are likely to change many aspects of their behaviour, and adapt and develop many of their attitudes and values as well. Some of these changes might be profound, and possibly last a lifetime. When students migrate to a new country, such changes can be even more dramatic. This paper looked specifically at ‘green’ behaviours and attitudes – those that relate to individual environmental impacts such as energy use, transport choices, and waste disposal, and specifically at Chinese students who come to study in the UK.

To collect data for this paper, my colleagues and I conducted qualitative focus group interviews with three groups of students: Chinese students in China (at the University of Xiamen), British students in the UK (at the University of Southampton), and Chinese students who had come to the UK to study (also at the University of Southampton). In total, we held seven focus groups with 46 participants.

We used ‘practice theory’ as our theoretical framework. Practice theory is a relatively novel way to think about the collective ways we do things (Scott et al, 2012; Shove et al , 2012). Practices – habitual ways we commute, eat, wash, cook, play sport, go on holiday, and so on – can be thought of as a combination of three elements: the meanings, competences, and materials involved in their ‘performance’. Competence refers to the ‘skill’ necessary for a given activity (for example, knowing how to recycle properly), materials refer to the physical ‘stuff’ required for it (e.g. access to recycling bins in your house or workplace), and meanings refer to the socio-cultural connotations or ‘image’ attached to it (e.g. thinking that it is important and worthwhile to recycle).

In our focus groups, it became clear that the three elements were more present and deeply embedded for the UK students than the Chinese students (that had stayed in China). To use the recycling example, the British students reported having far more experience of the ‘skill’ to recycle for many years compared to the Chinese students. They also reported having the ‘stuff’ to recycle – recycling bins, regular collection of plastic, glass etc, and the importance of recycling – the ‘image’ – was something that was ingrained in them from childhood. For Chinese students, these elements were not always present. In particular, the ‘image’ or ‘meaning’ element – the importance of recycling, was far from universal. Jing (a 21-year-old female Chinese undergraduate in the UK) illustrates the difference regarding ‘materials’ or ‘stuff’ which enables recycling:

“About litter sorting. I am quite environmentally-friendly I think so I do litter sorting. But in my home [in China] there are not corresponding boxes for different kinds of litters, but here [in the UK] I do ‘cause I see different boxes. So …”

For the third group – those Chinese students who had come to the UK – something interesting seemed to have happened after they migrated to study. Many students in this group said that they had changed their ‘green’ practices since coming to the UK. They had become far more likely to recycle and turn off lights, and less likely to litter or waste energy. The three elements were now present in their daily lives, in a way that had not always been true when they were at home in China. In particular, the ‘meanings’ or ‘image’ element was the one that changed the most. The students said that the cultural value of green behaviour in the UK which they observed among their western classmates and lecturers both on- and off- campus (their ‘community of practice’), led them to want to ‘fit in’. One participant Xiaoke (a 22-year-old female Chinese postgraduate in the UK) put it as follows:

“In China if everyone just throw litters around, and you put it in your pocket, it’s weird. But here everyone put it in pocket, then you won’t throw it around. It’s much like we say ‘thanks’ or ‘sorry’ more frequently here. Big social environment is important.”

The Chinese students who had come to the UK did not say that they suddenly had a revelation of the importance of being green, they just wanted to fit in. For those concerned by behaviour change, this is interesting because it suggests that the desire to fit in and be accepted by one’s peers – a process Bourdieu (1977) called ‘Mimesis’– might be more powerful than actively educating people to change.

I am now planning to build on these findings by looking at Chinese students who have studied in the UK and since returned to China. It will be interesting to see if behaviours revert back to the way they were before they left China, or if the green changes that arise from the time spent abroad are longer-lasting. In other settings, migrants are seen to ‘transmit’ the new attitudes they have learnt within a host country, along their transnational networks, and to their home communities (Nowicka, 2015). The scope for and power of such transmission might be greater for Chinese students who, after graduation, may go back to form the future social, economic, and political elites in their country. With around 60,000 Chinese students coming to UK universities each year, and many more studying in other Western universities, this group could potentially have a pivotal role to play in a future that is greener both for China and the wider world.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nowicka, M. (2015). Bourdieu’s theory of practice in the study of cultural encounters and transnational transfers in migration (No. ISSN 2192-2357). Göttingen. https://www.mmg.mpg.de/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/wp/WP_15-01_Nowicka_Bourdieus-theory.pdf

Scott, K., Bakker, C., & Quist, J. (2012). Designing change by living change. Design Studies, 33(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.08.002

Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How it Changes. London: Sage.

Author’s bio

Dr Roger Tyers is an ESRC-funded research fellow at the University of Southampton, based in the department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology. His interests are in behaviour change and public policy, particularly those behaviours and policies regarding the environment, energy, and transport. He can be contacted using R.Tyers@soton.ac.uk

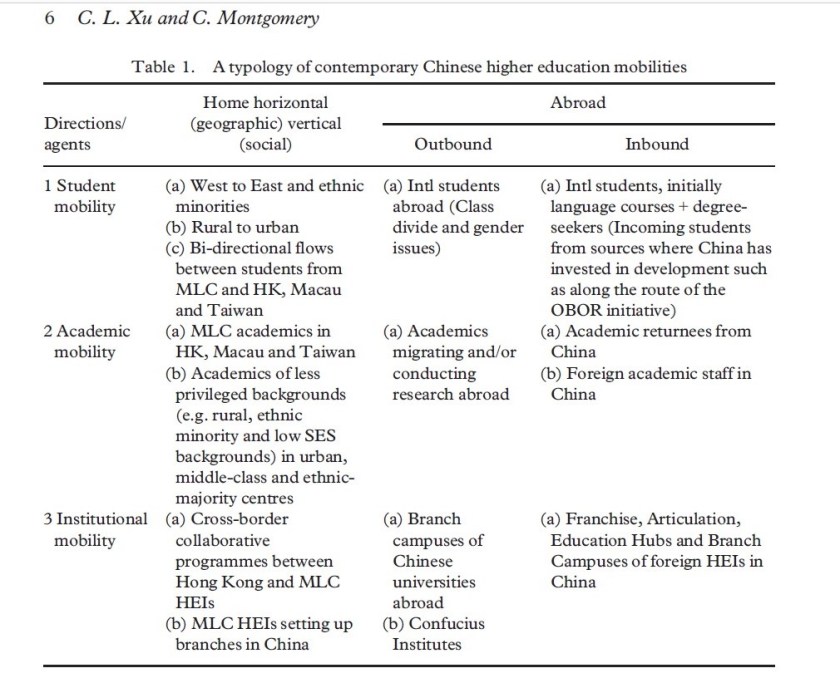

Educating China on the Move: A Typology of Contemporary Chinese Higher Education Mobilities

Listen to an earlier version of this paper presented at the Sociological Review Foundation sponsored seminar held at King’s College London in November 2017.

Xu, C. L., & Montgomery, C. (2018). Educating China on the Move: A Typology of Contemporary Chinese Higher Education Mobilities. Review of Education, 1-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3139 Context and implications document

Dr Cora Lingling Xu, Durham University

Abstract

The landscape of global higher education is changing rapidly in response to and alongside the geopolitical and geosocial global transformations, with China and East Asia becoming key players in higher education. As China’s economic power and strategic reach grows against a context of global uncertainty, it has become increasingly important to develop a nuanced understanding of Chinese globalisation, not least for its significance to the balance of power relations within and beyond Asia. Higher education provides a powerful lens through which to see how China is globalising and how this might impact on the world. This is manifested in its many established and newer forms of education mobilities. Recognising the lack of research efforts to systematically understand the complexities of contemporary higher education mobilities across China, this paper proposes a typology through a thematic narrative review of more than 250 peer-reviewed journal articles, government and media documents. This typology of Chinese higher education mobilities reveals three key insights, including (1) a critique on the ‘mobility imperative’ and the role of the Chinese state, (2) a call for more longitudinal and/or retrospective research to facilitate a relational understanding of the fluid nature of higher education mobilities in China, and (3) a note on the urgency of developing a

comprehensive theoretical and conceptual tool kit. This article contributes to an updated understanding of the fluid, multiple and multi-directional nature of contemporary higher education mobilities of China.

Context

Amid the fast-changing and highly mobile global higher education scene, Chinese higher education developments over the past decades have shown notable potential to challenge the traditional dominance of Western countries. To grasp the latest trends of higher education mobilities to, from, in and related to China, this article proposes a typology that encompasses nine prototypes of student, academic and institution mobilities. This typology is based on a systematic, narrative thematic review of more than 250 peer-reviewed journal articles, government and media documents, most of which published between 2010 and 2018. The purpose of this is twofold: firstly, to understand how movement of higher education is changing and developing around this important global power and secondly, to draw out implications for the rest of the world. The main implications of the article relate to the development of a nuanced picture of how education mobility is intertwined with complex social, cultural and geographic inequalities. It brings to the fore the significance of considering external higher education mobilities in conjunction with internal forms, emphasising the importance of recognising the dynamic, multiple and multi-directional nature of mobility and noting that education mobilities can be complex, circular or part of a ‘mobility chain’ effect where one sort of mobility can lead to another. This contribution is important not only in the context of China but in other emergent economies such as Mexico, South Africa and India.

Source: Xu and Montgomery (2018, p. 6)

Source: Xu and Montgomery (2018, p. 6)

Implications for Policy

The research underpinning this article demonstrates that there are changing patterns of educational mobility globally and China can be seen as being at the nexus of some of these changes. The article may have the following implications for policy

- The article’s detailed and nuanced analysis of higher educations mobilities to, from, in and related to China could influence ‘Western’ higher education institutions’ policy decisions around engagement with Chinese higher education institutions.

- One of the main contributions of this paper is its extensive literature review which focuses predominantly on constructing a non-western perspective by giving precedence to East Asian researchers and authors. As a result of this, the article could be influential in changing higher education policymakers’ western-centric views on China’s higher education mobilities.

- One of the article’s main contributions is a discussion of the rural and urban divide in China and how this relates to educational mobilities. A number of large emergent economies such as India and South Africa face challenges in socio-cultural and socio-economic divisions between rural and urban populations and this article could inform governments’ understandings of the relationships between these disparities and higher education mobility.

- The idea of mobility is frequently associated with social improvement and is sometimes seen as a panacea for social and cultural inequalities. The paper presents a critique of the ‘mobility imperative’, questioning the premise that mobility is necessary for social change. This could inform policy of governments and also NGOs working with marginalised communities.

Useful links

ScienceNet. (2017, 1 March). Ministry of Education Releases 2016 Statistics for Outgoing and Incoming Education in China [教育部发布2016 年出国留学和来华留学], ScienceNet.cn. Retrieved from http://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2017/3/369188.shtm

THES (2018). China could overtake US on research impact by mid-2020s. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/china-could-overtake-us-research-impact-mid-2020s . Accessed 13/07/18.

Authors recommend

Forsey, M. (2017). Education in a mobile modernity. Geographical Research, 55(1), 58-69.

Gao, X. (2014). “Floating elites”: Interpreting mainland Chinese undergraduates’ graduation plans in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Education Review, 15(2), 223-235.

Gu, Q., & Schweisfurth, M. (2015b). Transnational flows of students: In whose interest? For whose benefit? In S. McGrath & Q. Gu (Eds.), Routledge handbook of international education and development (pp. 359-372) (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge).

Hannam, K., Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). Editorial: Mobilities, Immobilities and Moorings. Mobilities, 1(1), 1-22. doi: 10.1080/17450100500489189

Hansen, A. S., & Thøgersen, S. (2015). The anthropology of Chinese transnational educational migration. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 44(3), 3-14.

Hayhoe, R., & Liu, J. (2010). China’s universities, cross-border education, and dialogue among civilizations. In D. W. Chapman, W. K. Cummings & G. A. Postiglione (Eds.), Crossing borders in East Asian higher education (pp. 77–100) (Hong Kong: Springer).

Leung, M. W. H. (2013). ‘Read ten thousand books, walk ten thousand miles’: geographical mobility and capital accumulation among Chinese scholars. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(2), 311-324. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00526.

Author’s short bio

Dr Cora Lingling Xu (PhD, Cambridge, FHEA) is Assistant Professor at Durham University, UK. She is an editorial board member of British Journal of Sociology of Education, Cambridge Journal of Education and International Studies in Sociology of Education. In 2017, Cora founded the Network for Research into Chinese Education Mobilities. Cora has published in international peer-reviewed journals, including British Journal of Sociology of Education, The Sociological Review, International Studies in Sociology of Education, Review of Education, European Educational Research Journal and Journal of Current Chinese Affairs. Her research interests include Bourdieu’s theory of practice, sociology of time, rural-urban inequalities, ethnicity, education mobilities and inequalities and China studies. She can be reached at lingling.xu@durham.ac.uk, and via Twitter @CoraLinglingXu.

The People in Between: Education, Desire and South Koreans in Contemporary China

Dr Xiao Ma, Leiden University, the Netherlands

Please find sections of my dissertation on Leiden University Repository

Abstract

This dissertation is an ethnographic research of three groups of people from South Korea to China — parents, students and educational agents — focusing on their desire regarding education. Examining this sheds light on the subjectivities of the people who are confronted with their structural positioning as being sojourners from South Korea and foreigners in China.

The individual desire on education is induced by and reflects China’s national ‘ambition’ in pursuit of educational internationalisation and Korea’s ‘compulsion’ to incorporate overseas nationals into its rhetoric of globalisation. Both nation-states confer political privileges on the children of overseas Korean nationals in their educational trajectories (e.g. preferential treatment in university entrance) by identifying them as potential international talents resources.

Consequently, students and people around them are empowered by the state discourse and gain legitimacy to creatively comply with, tactically appropriate, or, simply discard educational arrangements by the states. Paradoxically, they simultaneously encounter regulatory, socio-economic, and geographical constraints as they reside in China and make plans for further migration.

This thesis demonstrates that ethnic solidarity is restrictive in helping Koreans obtain opportunities that they expect to have. Koreans are increasingly scattered depending on their social-economic statuses and set out to merge with non-ethnics. This trait offers a significant insight into the nuanced tendency of the Chinese immigration policy.

中文摘要

该博士论文是一个研究三个韩国人群体的民族志,包括韩国父母,学生和教育中介,关注他们的教育渴望,并反映了他们面对‘暂居者’和’外国人’的结构性身份时表现出的主体性。中韩两国吸引人才和教育国际化的政策赋予了在华韩国人子女(以及与他们关联的群体)一定的特权,激发他们创造性地遵循,策略性地利用甚至忽视国家教育安排的主体性。同时,他们行为和认同也面临政策性,社会经济条件,和地理空间的限制和约束。此外,本研究发现,封闭的族群性对韩国人追求教育机会的作用是有限的,他们的行为和认知皆有跨越族群边界的趋势。

The people in between

This project understands South Koreans in China as ‘sojourners’ (ch’eryuja) and ‘foreigners’ (waiguoren), which are respectively identified by Korean and Chinese governments. This terminology represents a form of structural positioning endowed by the states, imbued with significant implications of favouring population mobility over settlement. I find that the government-defined terminology reflects rather than contrasts the migrants’ perceptions of the sending and receiving countries, which I call a form of ‘subject positioning’, also a status of ‘in between’ (Grillo 2007).

When making choices between different schooling systems and devising plans to go to universities in different national settings, parents and students are simultaneously sketching a cognitive map regarding the residence country, the homeland and the world beyond. Disengagement from home is conceived as a desirable opportunity to accumulate cultural capital in the younger generation; disintegration into the residence society is regarded as a preferable option to an undesirable destination. Homecoming is probably the ultimate goal, although this may be postponed due to intentions to pave the way for a smoother and more beneficial return to the homeland. The objective of remaining in the host society or re-migrating to a third destination is to be recharged overseas before returning to the highly competitive home country.

The art of being governed

Drawing on the term ‘the art of being governed’ (Szonyi, 2017), this project reveals the everyday politics between ordinary people and the state. I suggest that resistance is not the only strategy, so too is compliance. Migrant parents, students and agents learn and internalise national discourses and policies and convert them into their everyday concerns (Deleuze and Guattari 1983). It does not mean that individuals become ‘docile subjects’ who repress their desire and correspond their behaviour to social norms and political rules (Deleuze and Guattari 1983, 118). Rather, it unveils a capacity to learn and use state policies to one’s advantage, and ‘to borrow the state’s legitimacy and prestige and turn it into a political resource for one’s own purposes’ (Szonyi 2017, 221). In doing this they decide when to comply with, how to appropriate and whether to ignore state regimes. Moreover, they are able to choose which country’s policy to follow. Thus, they become subjects who tactically indulge or tame, intensify or reduce, consist in or convert their desire between different state regimes. They explore, learn and practice ‘the art of being governed’.

Being identified as potential ‘international talents’ and ‘global human assets’, the Korean students in my study are manpower highly valued in the state’s political agenda. Their mobility is indispensably supported and conditioned by their parents and the educational agents. Given the political significance imposed on students, they and the people who facilitate their movements are substantially differentiated from the politically subordinated people. They are authorised by the national rhetoric and become intimately connected with the state and capable of appropriating policies to their advantage. This demonstrates Michel Foucault’s vantage point on desire and power: the sovereignty of nation-states, as a terminal form that power takes, is by no means external to individuals and their subjectivities, rather it constitutes an integral part of them (Foucault 1978, 92).

Ethnicity and class

In general, a conspicuous sense of ethnic solidarity within each group of parents, students and educational agents failed to be manifested. Rather, they scrambled to gain more benefits and circumvent possible loss by making discursive and practical boundaries with their counterparts: expat and non-expat parents, good and bad students, illegal and exemplary businesses. A host of competition, comparison and differentiation were shown in the intra-ethnic interactions. This denotes that the extensive emphasis on ethnic origin and cultural heterogeneity is restrictive in helping Koreans obtain the socio-economic opportunities that they expect to have, which I call a process of de-territorialised ethnicity. This is not indicative of a dysfunction of ethnic institutions such as Korean schools and private-run education institutes. Rather, considerable numbers of students were reliant on the ethnic institutes in the pursuit of their dream universities in Korea, China or a third destination. To meet student demands, ethnic education agents were required to mediate multiple interest groups by transcending ethnic and national boundaries (e.g. collaboration with Chinese schools and universities).

This de-territorialisation of ethnicity occurs simultaneously alongside another tendency that I term as re-territorialisation of class. Despite being homogeneously defined as middle-class in the home country, Koreans in China developed dynamic and specific identities to differentiate their social position from other members of this group. Their identification is derived from their employment status (as expats and non-expats), income, and consumption pattern (e.g. the type of school a child attends or the neighbourhood where a family resides). As a consequence, fragmented Korean ethnic groups established connections and identified with non-ethnic counterparts such as Chinese and/or other foreigners.

References

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1983. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1978. The History of Sexuality Volume I: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Pantheon Books.

Grillo, Ralph. 2007. “Betwixt and Between: Trajectories and Projects of Transmigration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (2): 199–217.

Szonyi, Michael. 2017. The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China. Princeton University Press.

Author’s short bio

Dr Xiao Ma holds a Master’s degree in Sociology from China Agricultural University in Beijing. In 2018, she obtained her PhD in social anthropology from Leiden University in the Netherlands. Her research interests include anthropology and sociology of migration, transnationalism, migration and education, migrant and nation-state, ethnicity and class. She carried out fieldwork in China, South Korea and in the Netherlands. Her book chapter entitled ‘Educational Desire and Transnationality of South Korean Middle Class Parents in Beijing’ was published in Destination China: Immigration to China in the Post-reform Era, edited by Angela Lehmann and Pauline Leonard, Palgrave Macmillan, in 2018. Xiao can be contacted via email at maxiao8784@gmail.com.