Research Highlighted:

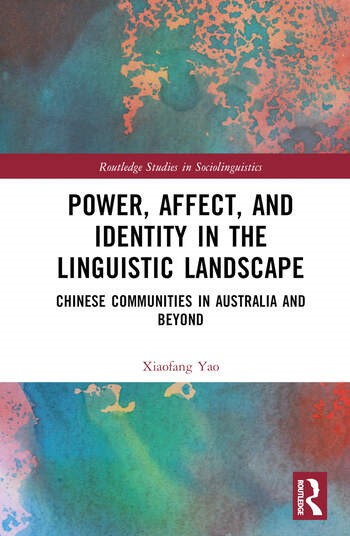

Yao, X. (2024). Power, Affect, and Identity in the Linguistic Landscape: Chinese Communities in Australia and Beyond (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003320593

Introduction:

Uncovering the complexity of linguistic diversity and semiotic creativity, this book examines the issues of power, affect, and identity in both physical and digital linguistic landscapes.

Based on fieldwork with various Chinese communities in Australia, the book offers unique insights into the uses of languages, semiotic resources, and material objects in public spaces, and discusses the motives and ideologies that underline these linguistic and semiotic practices. Each chapter frames the sociolinguistic issue emerging from the linguistic landscape under investigation and shows readers how the personal trajectories of individuals, the availability of semiotic resources, and the historicity of spaces collectively shape the meanings of publicly displayed language items in offline and online spaces. Supported by a wealth of interviews, media, and archival data, the book not only advances readers’ understanding of how linguistic landscape is structured by various historical, political, and sociocultural factors, but also enables them to reimagine the linguistic landscape through the lens of emerging digital methods.

Ideal Audience: This book is an ideal resource for researchers, advanced undergraduates, and graduate students of applied linguistics and sociolinguistics who are interested in the latest advances in linguistic landscape research within virtual and material contexts.

Chapter Highlights:

1. Situating Power, Affect, and Identity in the Linguistic Landscape: This introductory chapter sets the stage by explaining the concept of the linguistic landscape and the latest theoretical developments in the field. It focuses on three key sociolinguistic constructs—power, affect, and identity—and explores how a linguistic landscape approach, with its distinctive visual, spatial, and material lens, can offer new insights into these issues. The chapter also provides a brief overview of Chinese communities in Australia to establish the social, cultural, historical, and political contexts for the case studies presented in the book.

2. Theoretical perspectives on the linguistic landscape: Geosemiotics, sociolinguistics of globalisation, and metrolingualism: Linguistic landscape studies often draw on theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches from various disciplines. This chapter addresses the challenge of framing, scoping, and operationalizing a linguistic landscape study by redefining the field’s ever-expanding scope. It reviews seminal works by scholars such as Ron Scollon, Suzie Wong Scollon, Jan Blommaert, and Alastair Pennycook to provide a robust theoretical framework. This framework integrates geosemiotics, the sociolinguistics of globalization, and metrolingualism, emphasizing the importance of material objects and the materiality of language in constructing meaning. The chapter underscores the posthumanist approach in uncovering critical issues related to language, culture, and society.

3. Affect in the linguistic landscape: Conviviality and nostalgia in urban and rural ethnic restaurants: This chapter delves into the emerging field of visceral linguistic landscapes, which investigates the evocative potential of space and how linguistic landscapes can regulate human emotions. It presents a case study of two Chinese restaurants—one in a rural area and the other in an urban setting—to explore how material objects in these spaces evoke feelings of nostalgia and conviviality. By examining elements such as paintings, menus, emblems, and decorations, the chapter reveals how spaces are social and historical constructs that reflect the memories of Chinese migrants and their connections to an imagined community. It also shows how these spaces are agentive, shaping and curating affective experiences.

4. Power in the linguistic landscape: Tourism and commodification as revitalisation of cultural heritage: Power dynamics are a central theme in linguistic landscape research, often studied through the lenses of language policy and ideologies. This chapter goes further by exploring the agency of language, space, and material conditions in shaping, confronting, and resisting power. It examines the interactions between local authorities and the Chinese community in a diasporic context, focusing on the commodification of language and the revitalization of cultural heritage. Through narrated stories, semiotic artifacts, and cultural rituals, the chapter uncovers the tensions between ethnic identity pride and the commercial interests of ethnic tourism, highlighting the motivations and attitudes of stakeholders in the linguistic landscape.

5. Identity in the linguistic landscape: Metrolingualism at the online-offline nexus: The rise of social media has prompted linguistic landscape researchers to consider digital spaces alongside physical environments. This chapter adapts the theory of metrolingualism to analyse how the Chinese diaspora constructs identity on platforms like WeChat. It examines the linguistic and semiotic resources used for self-presentation and identity performances, revealing the ideologies and aspirations behind these practices. The study highlights how hybrid identities challenge traditional notions of ethnicity and showcase the fluidity of identity in the online-offline nexus, where social conventions from offline spaces influence online interactions.

6. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the linguistic landscape: An agenda for critical digital literacy: Artificial intelligence is transforming the broader field of applied linguistics, including linguistic landscape research. This chapter explores the potential of AI tools, such as ChatGPT, in conducting linguistic landscape studies. It reviews current computational approaches and discusses the levels of critical digital literacy required for researchers in an AI-driven future. By experimenting with AI models, the chapter illustrates how AI can serve as both a tool and a collaborator, assisting with literature reviews and qualitative coding of photographic data. It emphasizes the need for linguistic landscape researchers to understand and critically engage with AI technologies to enhance their work.

7. Transcending boundaries in the linguistic landscape: Towards collaborative, participatory, and empowering research: This concluding chapter synthesizes insights to develop frameworks for understanding power, affect, and identity in the linguistic landscape. It emphasizes transcending boundaries between communities, spaces, and languages, challenging the notion of ethnic enclaves, and recognizing community fluidity. The chapter advocates for research with a stronger temporal and spatial focus, examining interactions between physical and digital linguistic landscapes. It calls for collaborative, participatory, and empowering research approaches to ensure community goals, values, and voices are incorporated, highlighting the importance of community engagement and the transformative potential of inclusive research methodologies.

Author bio

Xiaofang Yao, The University of Hong Kong

Xiaofang Yao is Assistant Professor in the School of Chinese, The University of Hong Kong. Her research areas include linguistic landscapes, multilingualism, social semiotics, and sociolinguistics. She is particularly interested in the intersection of language, culture, and space as they relate to the Chinese diaspora and ethnic minorities. Her current projects explore the representation of Chinese languages and semiotics in diasporic contexts, as well as the negotiation between standard language norms and creative or transgressive language practices among ethnic minority communities in Hong Kong and Southwest China.

Managing Editor: Xin Fan