Research highlighted:

Xin Xu (2020). Performing ‘under the baton of administrative power’? Chinese academics’ responses to incentives for international publications. Research Evaluation, 29(1): 87-99. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz028

Xin Xu, Heath Rose & Alis Oancea (2019). Incentivising International publications: institutional policymaking in Chinese higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 1-14. http://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1672646

Xu, X. (2019). China ‘goes out’ in a centre-periphery world: Incentivising international publications in the humanities and social sciences, Higher Education, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10734-019-00470-9

The research context: Incentives for HSS international publications

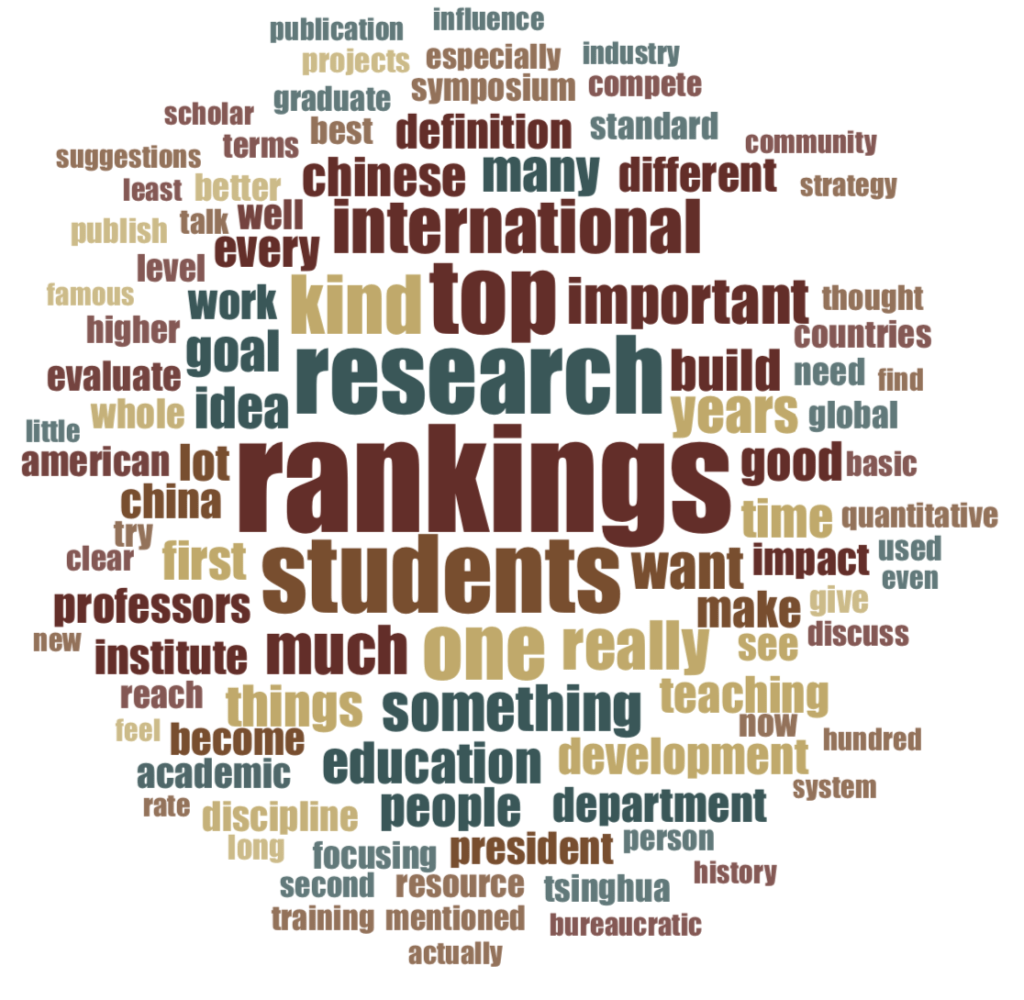

Publications in internationally-indexed journals are becoming essential for global university rankings, institutional assessments, and academics’ career development (Ammon, 2001; Hazelkorn, 2015; Hicks, 2012). China is taking the lead in the volume of such publications in global science and technology, ranking first as a single country in terms of science and engineering publications (US National Science Foundation, 2018).

However, its international publications in the humanities and social sciences (HSS) are still less visible in the world (Liu, Hu, Tang, & Wang, 2015). In response, many Chinese universities have formulated incentive schemes to offer financial rewards and/or career-related benefits to encourage HSS academics to publish internationally (Xu, Rose, & Oancea, 2019). Such incentives are growing rapidly, which has provoked heated debates (see for example: Dang, 2005; Qin & Zhang, 2008).

Research methods

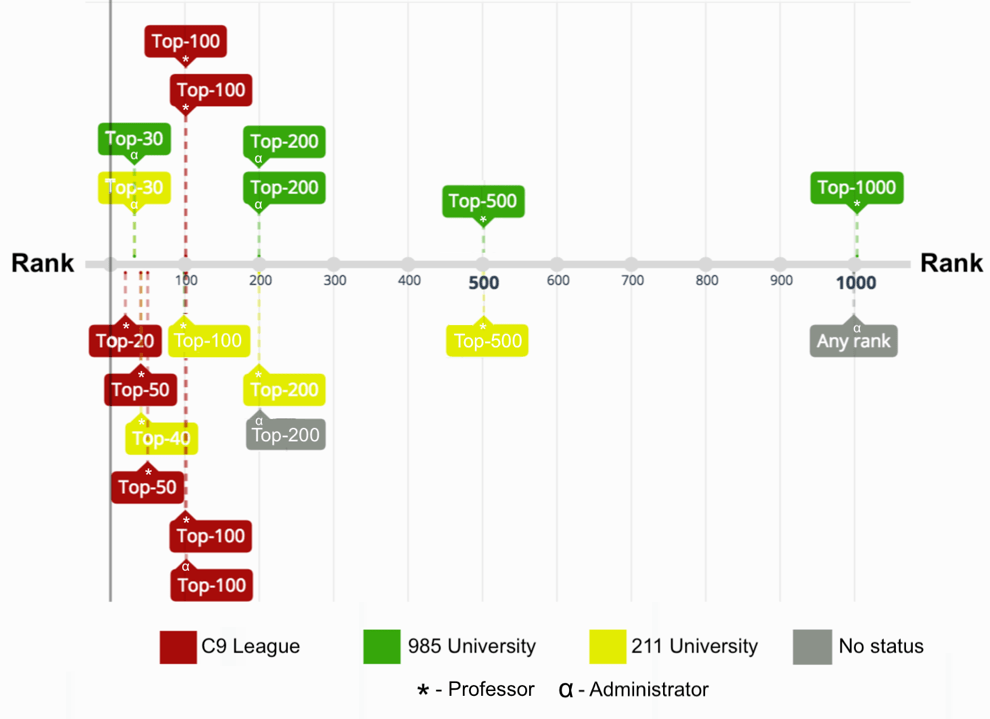

Dr Xin Xu’s doctoral research examined how Chinese universities have attempted to incentivise academics in the HSS to publish in internationally-indexed journals, and how such incentives have influenced HSS academics’ research and careers. It drew on a documentary analysis of 172 institutional policies and a qualitative case study of six universities in China, including 75 in-depth interviews with HSS academics, university policymakers, and journal editors.

This article reports findings from three recent publications based on the thesis.

Research findings

A national landscape of incentivising HSS international publications

The research found that by 2016, 84 out of all 116 universities designated as ‘985’ and ‘211’ in China had formulated university-level incentive schemes (Xu et al., 2019). They provided financial rewards and/or career-related benefits to encourage HSS publications in internationally-indexed journals. The publication-related incentives varied in their aims, in the level of benefits, and in the specific requirements. However, higher prestige was often attached to publications in international journals indexed by the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI). Compared with publications in Chinese-medium journals, SSCI and A&HCI publications were associated with higher bonus value and higher status in academics’ career development (Xu et al., 2019).

Take the bonus values for instance. Among the 172 incentive documents collected, 94 documents had provisions for giving monetary bonuses for SSCI publications, 78 documents provided monetary bonuses for A&HCI publications, and 61 documents offered bonuses for publications in Chinese HSS journals. Among them, 54 also offered special bonuses for publications in Nature and Science, and 59 provided bonuses for SCI publications. The bonus value varied between publications in different types of journals: SSCI and A&HCI publications, CSSCI publications, and SCI publications. Table 1 shows the hierarchical bonus values attached to different kinds of publications.

Influences of the incentive schemes

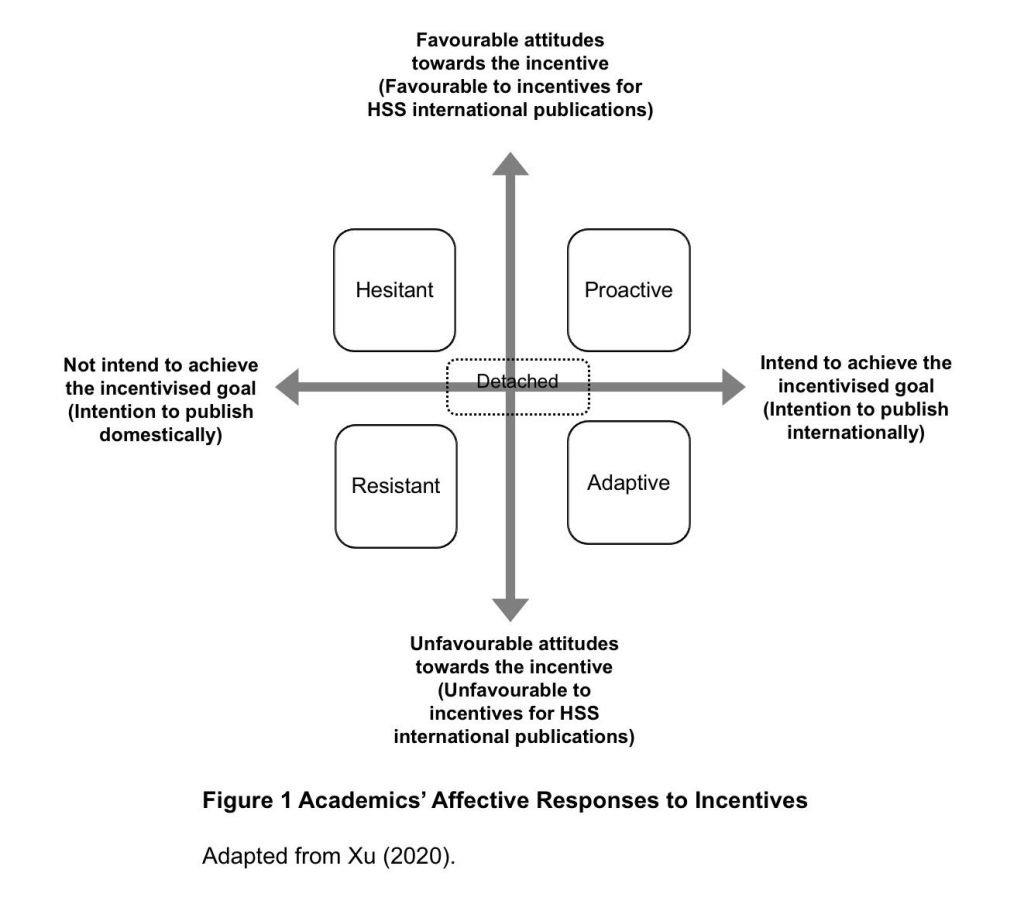

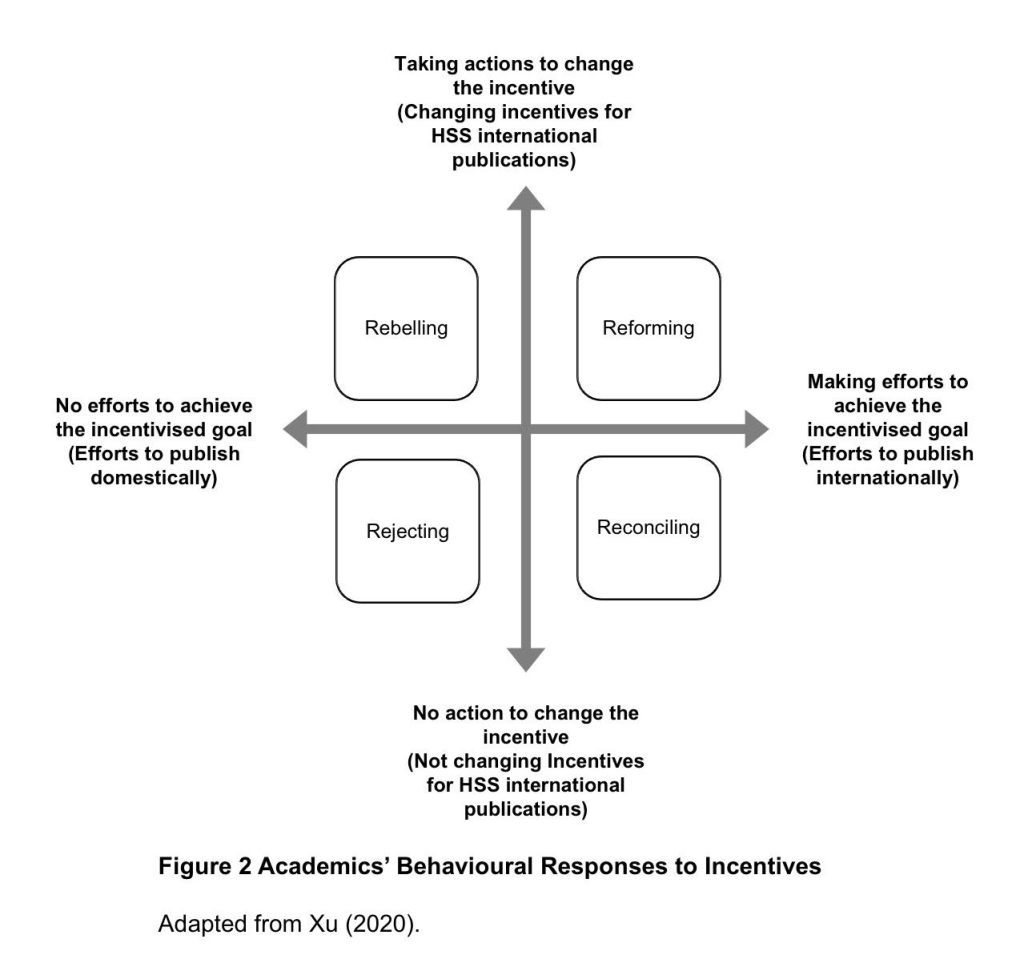

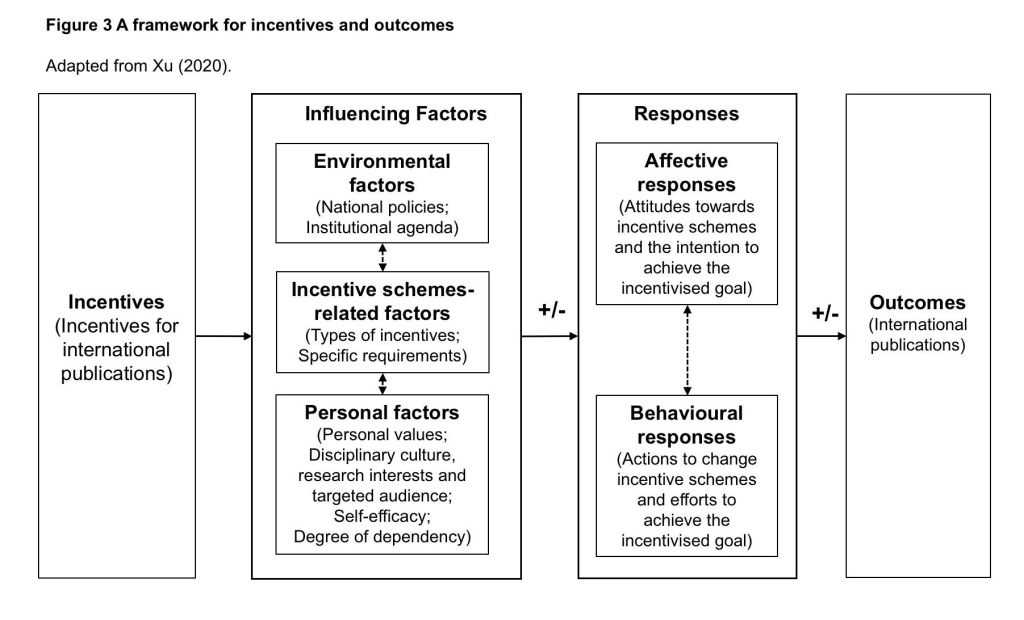

Xu (2020) proposes two typologies to categorise academics’ affective responses (proactive, adaptive, resistant, hesitant, and detached) (see Figure 1) and behavioural responses (reconciling, rejecting, reforming, and rebelling) (see Figure 2) to research incentives. Academic interviewees from different sub-groups and various backgrounds demonstrated mixed responses, and reported that incentive schemes had direct and indirect impacts on their research (see Figure 3) (Xu, 2020).

Some of the influences of incentive schemes appeared to be undesirable. For example, incentive schemes could create a ‘Matthew Effect’ in global HSS publishing, enabling SSCI and A&HCI journals to flourish, while deepening the divide between these and other journals (Xu et al., 2019). If constantly imposed through administrative and managerial power, external incentive schemes could also challenge the intrinsic value of academic research, thus putting academics’ agency at risk (Xu, 2020).

Dynamics between the internationalisation and indigenisation of HSS

Incentive schemes also reflect the dynamics between the internationalisation and indigenisation of Chinese HSS. As showcased by the data, there is a ‘going-out’ in theory and ‘borrowing-from-the-west’ in practice. While incentive schemes were initiated to promote the ‘going-out’ of Chinese HSS, they were formulated and implemented with the heavy adoption of Western norms and standards. Those norms are not unchallenged in Western contexts, such as the value and use of impact factors, and the linguistic, geographical, and cultural inequity in citation indices like SSCI. However, the research revealed a lack of critical engagement with those debates from Chinese universities (Xu et al., 2019).

The prestige of international publications in China has reinforced inequities in the international publishing regime, being associated with a hierarchical divide in global HSS academia, and generated disincentives for HSS academics to publish work focused specifically on local/national concerns, or work that generated original indigenous theorisations or methods not part of prior global literature. Moreover, HSS research is contextually rooted in certain cultures, languages, and traditions. Consequently, prioritising publications in international journals (mostly English-language journals published in global knowledge centres) could impair the development of domestic HSS (Xu, 2019).

However, the research has identified specific dynamics in Chinese HSS, which challenge the ‘centre-periphery’ model commonly used to describe the hierarchical divide in the global knowledge system and explain lower income countries’ dependency on more economically advanced countries in their research economy. For instance, some academics called for a more proactive role promoted by Chinese scholars in asserting distinctively Chinese ideas. There is an increasing number of HSS academics engaging substantially with international journals as reviewers and editors, thereby becoming more active global agents in their own right. Meanwhile, some universities had revised their incentive documents to enhance the value ascribed to the leading domestic publications (Xu, 2019).

The study has practical implications for government and institutional policymaking, which apply not only to China, but to other countries traditionally associated with the global ‘knowledge periphery’, especially other non-English speaking countries. In particular, it suggests that strategies to internationalise HSS should not simply seek to adapt to what is perceived as the global knowledge centre, nor simply to reproduce the hierarchies in domestic academia. In China, one of the unintended effects of current incentives was to reinforce the peripheral status of Chinese HSS in the domestic domain. Alternatively, universities could work to challenge the unequal power relations within global HSS. This calls for more attention to the balance between international and indigenous knowledge, and the balance between English-language publications and publications in other languages, particularly in the mother tongue language (Xu, 2019).

Acknowledgements

The research leading to this article has been generously funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant number: ES/T006153/1); Clarendon Fund, University of Oxford; Universities’ China Committee in London Research Grant; Santander Academic Travel Awards, University of Oxford.

Authors’ biography

Dr Xin Xu (许心) is an ESRC Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Global Higher Education, Department of Education, and a Junior Research Fellow at Kellogg College, University of Oxford. She completed her doctoral research at the University of Oxford, examining the incentives for international publications in the humanities and social sciences, and their impacts on academics’ research and careers. She has strong research interests in higher education, internationalisation and globalisation, academic and research life, and research assessment and impacts.

Email: xin.xu@education.ox.ac.uk Twitter: @xinxulily

Dr Heath Rose is an Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics, who researches the impact of globalisation on English language education in higher education. He has conducted policy-related research in Japan and China surrounding the ‘Englishisation’ of international programs. He has authored several books associated with globalisation and language education.

Email: heath.rose@education.ox.ac.uk

Prof. Alis Oancea is Professor of Philosophy of Education and Research Policy and Director of Research in the department. Her research has focused on: research on research, including research policy and governance, research assessment and evaluation, incentives and criteria for worthwhile research (including openness, quality, impacts, ethics), and research capacity building; higher education policy and reform; teacher professionalism and teacher education in international contexts; philosophy of education; empirical, and philosophical exploration of different modes of research and methodological theory; and the cultural value of research in the arts and the humanities. Alis is the joint editor of the Oxford Review of Education, and was founding editor of the Review of Education.

Email: alis.oancea@education.ox.ac.uk Twitter: @ciripache

References

Ammon, U. (Ed.). (2001). The dominance of English as a language of science: Effects on other languages and language communities. Berlin; New York: Berlin : Mouton de Gruyter.

Dang, S. (2005). Meiguo biaozhun neng chengwei Zhongguo Renwensheke chenguo de zuigao biaozhun ma?——Yi SSCI weili. [Can American standards set the highest evaluation benchmark for Chinese Social Sciences? – Take SSCI as an example]. Social Sciences Forum, 4, 62–72.

Hazelkorn, E. (2015). Rankings and the reshaping of higher education: The battle for world-class excellence (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hicks, D. (2012). Performance-based university research funding systems. Research Policy, 41(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.007

Liu, W., Hu, G., Tang, L., & Wang, Y. (2015). China’s global growth in social science research: Uncovering evidence from bibliometric analyses of SSCI publications (1978–2013). Journal of Informetrics, 9(3), 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2015.05.007

Qin, H., & Zhang, R. (2008). SSCI yu gaoxiao renwenshehuikexue xueshupingjia zhi fansi [Reflections on SSCI and academic evaluation of Humanities and Social Sciences in higher education institutions]. Journal of Higher Education, 3, 6–12.

US National Science Foundation. (2018). Science and engineering indicators 2018: Academic research and development.

Xu, X. (2019). China ‘goes out’ in a centre–periphery world: Incentivizing international publications in the humanities and social sciences. Higher Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00470-9

Xu, X. (2020). Performing under ‘the baton of administrative power’? Chinese academics’ responses to incentives for international publications. Research Evaluation, 29(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz028

Xu, X., Rose, H., & Oancea, A. (2019). Incentivising international publications: institutional policymaking in Chinese higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1672646